Teaching an Aspie to Drive: #2 Driving Protocols for Safety and Efficiency

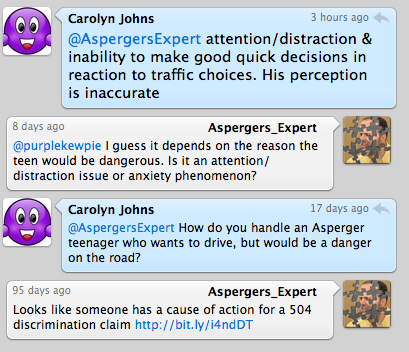

I responded to a twitter question and had the following exchange:

So the real answer needs more than 140 characters.

This is the second in a series. Read the first post for context.

PROTOCOLS: What are the rules of the road?

For many Aspies, passing the written driving test will be a breeze. It has limited number of objective answers and they're all available in the drivers' manual. In short, the written test shouldn't be so hard. But that's like saying that reading Emily Post is enough to guarantee relational success. It won't. Use this example to help the Aspie pre-driver keep their test-born confidence in check.

Here are some basic protocols to help the Aspie driver be safe.

- 1. Driving is not operating a predictable machine. Driving is a team sport with unpredictable humans.

- 2. Driving is not an isolated behavior, it is a highly social combination of behaviors, attitudes, and communications.

- 3. Driving safely depends on fluency in a language of symbols and behaviors.

- 4. The status quo is usually safest.

To elaborate:

Protocol 1. We tend to think that machines are reliable, mechanical and predictable. Because driving is operating such a machine, it is reasonable to misapply mechanical rules to the experience of driving. However, the most significant variable in driving isn't the car—it's the driver. Cars don't cause accidents, people do. Since most of us with Asperger's have a pretty firm grasp on the unpredictability of humans, this approach can be a good entry to the difficulty of driving. The most important part of this protocol is to introduce and reinforce the idea that many drivers don't follow the rules. They change lanes without signaling. They run red lights. They speed, honk, swerve, stop, and cut you off without warning. Driving defensively isn't quite enough. We need to drive with a healthy slice of paranoia about the capability and character of other drivers.

Which leads to protocol 2. Driving is highly social. You can help your learning driver by spending time alone with them in the car articulating all the behaviors you can anticipate, infer, and observe about other drivers. You can show how the speed, position, and stability of a car give you clues to the driver's intent. For example, if I am driving in left lane of a freeway and a driver enters in the lane to my right, there is a reasonable chance that the entering driver will want to merge into the fast lane. That chance increases significantly if the driver enters the freeway behind a semi truck or some other slower vehicle. If a driver enters the freeway behind a semi and starts drifting toward the lane line I can almost guarantee an imminent lane change. The combination of entering driver + behind traffic + drifting to the lane is more reliable than a turn signal.

So then, protocol 3 is that driving has many symbols and behaviors that comprise a web of communications.

Many of the symbols are explicit, such as road signs, traffic signals, speed limits, turn signals, lane markings, and all of the gauges and dials in the car. Many people with Asperger's will rely too much on these explicit symbols because they are more concrete and reliable. The other set of symbols, and arguably the more important set, are implicit. Most of the implicit signals are more subtle and are context-dependent. For example, speed limits are more rigid in the presence of a marked patrol car. Drivers are more aggressive at rush hour as the traffic load slows them down. Mini-van drivers are less likely to cut you off than sports sedan pilots. In addition to all the subtle driver hints (swerving = distracted; slowing = uncertainty; sudden changes = impulsive; tailgating = impatience) there are environmental cues as well. Traffic around schools will slow down before and after school.

Just as human interactions are governed by a multitude of subtle cues from head tilts to eye rolls, driving is enmeshed in a web of signals and symbols that must first be recognized and then correctly understood. People with Asperger's are very capable of learning to recognize implicit signals. They are less likely to interpret them correctly on the fly. That said, experience does make us better at correctly translating and responding to even implicit cues.

Finally, protocol 4 is embrace the status quo. Think in terms of maintaining the safe circumstances. Almost any change can be dangerous. Changing speed, lanes, changing your planned route, changing the radio station, reclining the seat, drinking a soda—all these are changes, and changes are risky. When you are actually practicing behind-the-wheel, introduce imaginary crises such as, "You missed the turn!" or "There's an accident on your right!" or "A ball just bounced into the road." In most cases, the safest course of action is to slow slightly while scanning aggressively for any relevant information. Help the learning driver understand how adding change to the equation diminishes their ability to respond safely to driving dynamics.

image via kaykays.com

image via kaykays.com